Stonehenge is like a church in a big city. Most likely this church has been built before Roman times but currently will house modern apartments, or a movie-theater, a concert venue, an art gallery or will still be in function as a church. In other words, the building shows how adaptable it is to different social needs. Stonehenge has a much longer but equally varied succession of functions.

I take the freedom to bring artistic interpretations to the scene, alongside with archaeological references, because Stonehenge is such powerful visual icon. Visiting Stonehenge offers a different experience compared to overgrown Neolithic hill-forts like Tara Hill in Ireland. Stonehenge’s visual impact has, since it first days, not lost any of its appeal. It has inspired artists, writers, and photographers and it is therefore justifiable to include artworks in this assignment. Next to art resources, ‘Researching Stonehenge; Theories Past and Present’, by Mike Parker Pearson has providing me with an overview of research done at Stonehenge as well as evolving insights into rituals functions of Stonehenge.

A 14th Century Print with Merlin Building Stonehenge

In this 14th century print we see Merlin, as an unshaven giant, helping humans building Stonehenge. Geoffrey of Monmouth (1100-1155) thought that Stonehenge was originally built in Ireland by giants and was later relocated to Britain to function as a temple for ancient druids. The temple function of Stonehenge was confirmed in Roman times by Hecateus who assumed Stonehenge to be a temple for honouring Apollo. John Aubrey/William Stukeley, both mid-17th century, proposed a likewise theory. Aubrey and Stukeley thought Stonehenge was built before the Romans. Stukeley, a member of Freemasonry, even took druidry up himself and attempted to date Stonehenge for the first time. He wrongly ascribed the building of Stonehenge to druids. Later, Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley (1851–1941), a British archaeologist undertaking pioneering excavations at Stonehenge, followed Stukeley’s theory Stonehenge was indeed a temple, for priests and for nobles.

Despite archaeologists disapproving with Stonehenge as a ‘temple of the Druids’ as modern dating methods indicate that Stonehenge was built long before the time of the Druids, up to today druid-style dressed up visitors celebrate the summer solstice at Stonehenge.

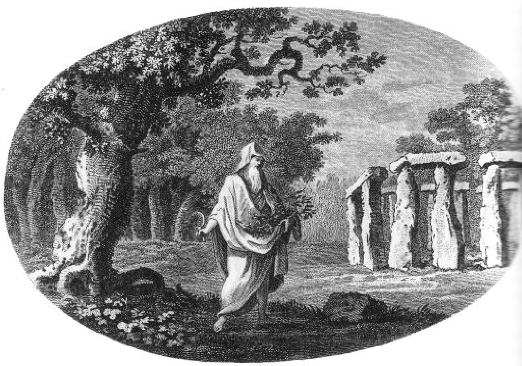

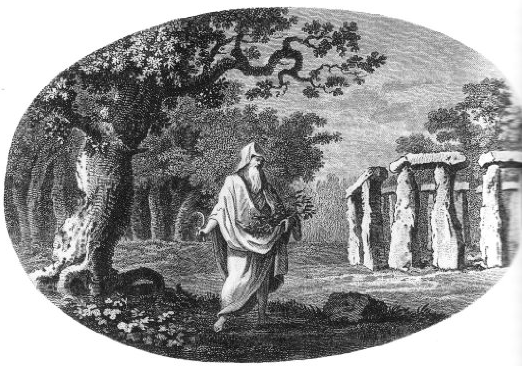

Stonehenge as imagined in Francis Grose

Returning to the suggested relation between druids and Stonehenge, I present this engraving which shows a druid holding mistletoe and a sickle. The druid obviously has collected mistletoe and is now turning towards Stonehenge. What connects druids, mistletoe and Stonehenge? Mistletoe was regarded a sacred herb as it grows without soils between heaven and earth. Mistletoe growing on oak tree is rare, which has been noticed and utilized in the Celtic world. Gaius Plinius Secundus (23-79 AD), a Roman author also known as Pliny the Elder, describes a Celtic ritual sacrifice at which a druid, dressed in white, climbs an oak tree collecting mistletoe with the help of a sickle. This was done with great ceremony on the sixth day of the moon, by using a golden coloured sickle. Mistletoe, according to druids, as recorded by Pliny the Elder, increased fertility of cattle. This could have been important to Salisbury farming communities. Old theories, by Geoff Wainwright and Francis Grose both connecting Stonehenge to Druidic practices, stressing healing properties, re-emerge in 2006 when Tim Darvill uses the studies of Wainwright where he theorizes that Merlin collects the blue-stones from Ireland because of their healing properties. There is no archaeological evidence that Stonehenge blue stones were relocated from Ireland. They come from West-Wales’ Preseli Hills. Thus the theory changes but keeps Stonehenge associated with healing rituals because Preseli’s holy wells were believed by Medieval people to offer healing water. Water throw against the blue stones of Stonehenge likewise resulted in to empowering water with healing properties. Up till the 18th century visitors of Stonehenge chiselled off pieces of blue stones believing these pieces to have curative powers. Stonehenge’s healing hypothesis has survived the test of time despite that its focus changed from mistletoe utilizing healing rituals to healing properties of Stonehenge’s blue stones.

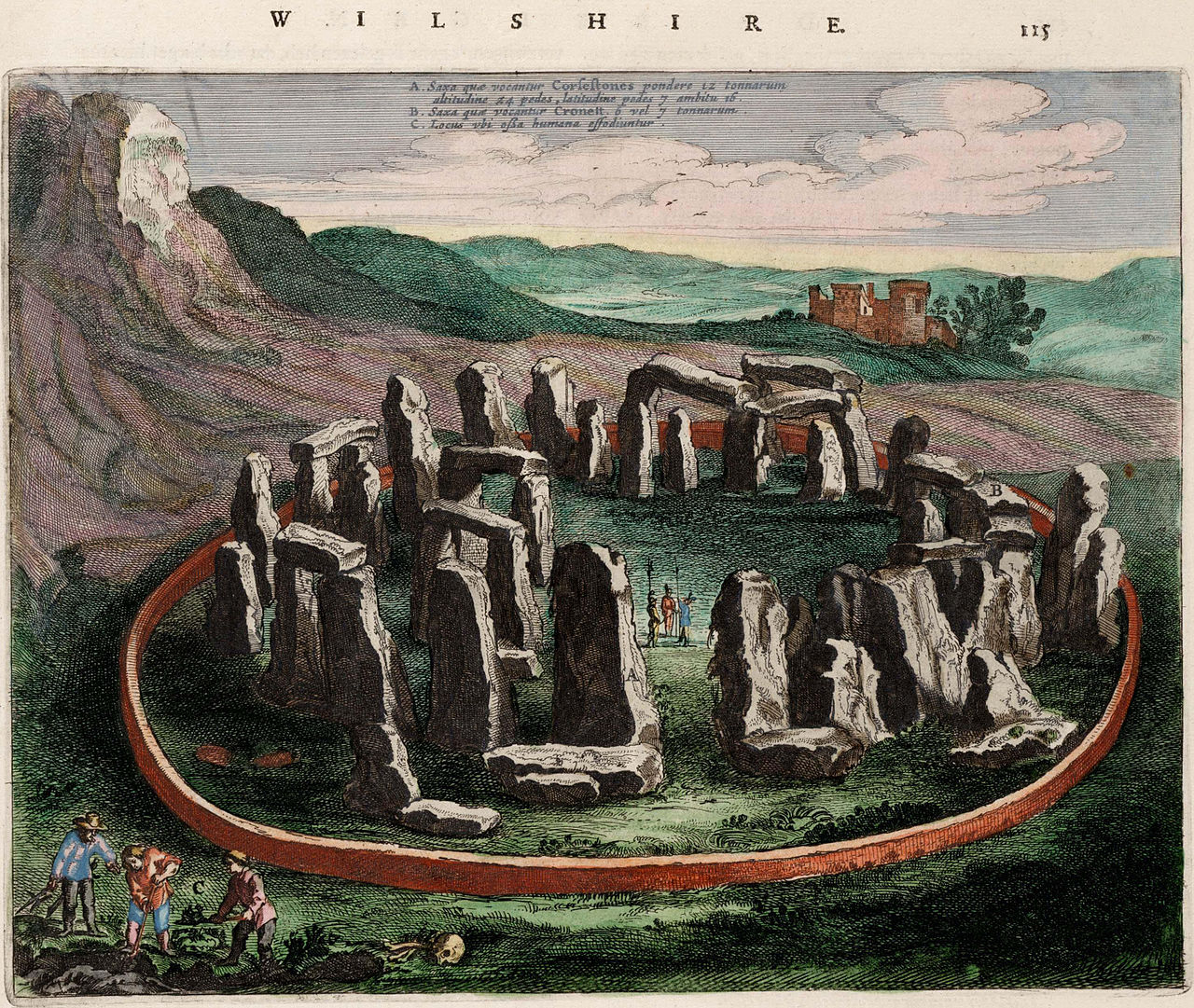

Wiltshire, a stylized 1700s look at Stonehenge

The artist of this etching or drawing, shows two groups of people as such expressing two different ritual functions of Stonehenge. There is a clear distinction in fashion between the men standing within Stonehenge circular structure and those who are working at the front. The artist shows neatly dressed men as researches, noblemen or landowners within Stonehenge. More importantly, brought to the front, are (probably) grave robbers. They have just unearthed a skull and three large bones. Hence, Stonehenge is depicted in its function as a place of (elite) interest, as well in its sepulchral function as it is surrounded by interesting burials that are worth robbing. It doesn’t comes as a surprise that only a skull and some large (human?) bones are found in Stonehenge’s ditch as in Neolithic times human and animal bones were offered or buried in ditches or under buildings. It was William Flinders Petrie, working on Stonehenge between 1874-1880, who suggested that Stonehenge’s function was ‘sepulchral, religious, astronomical and monumental’.

In the 1920s Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley (1851–1941), a British archaeologist digs up nearly 60 cremated and uncremated human remains inside Stonehenge; the remains are reburied in 1935. Hawley’s excavations confirm Stonehenge’s funerary function. In 2002 of the grave of the Amesbury Archer, 3 miles from Stonehenge, is found by archaeologists from Wessex Archaeology. The grave dates back to 2,300 BC and is richest array of items ever found from this period thus leading to the believe that the archer possibly was the King of Stonehenge.

In 2007 the Stonehenge Riverside Project and the Beaker People Project radiocarbon date surviving skeletal remains. This results in establishing Stonehenge’s cemetery function as from the early third millennium BC. Interpreting Stonehenge’s ritual function, as far back as the 1700s, as a burial place that has seen different funerary rituals and mortuary practices has thus been supported by past and recent (2007) archaeological research.

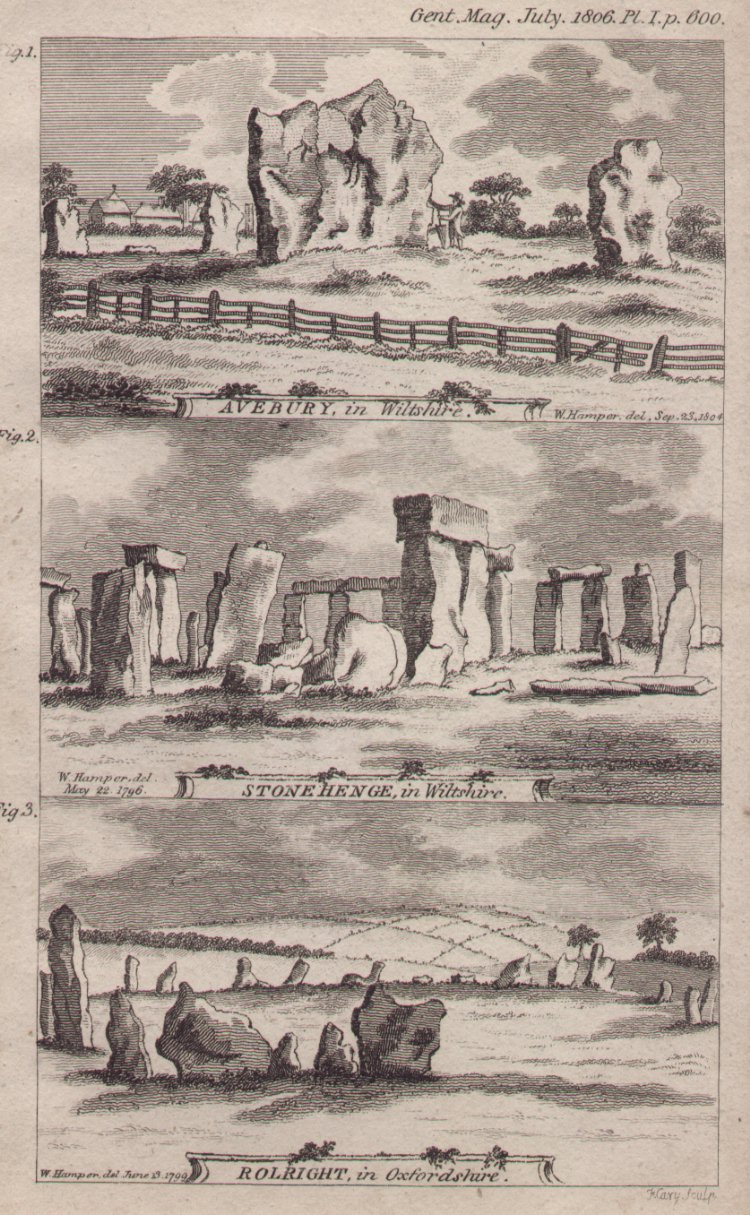

Avebury, Stonehenge and The Rollright Stones 1806

As far back as in 1806, somebody with drawing skills, connects Avebury, Stonehenge and the Rollright stones in Oxfordshire. Later, long-term multidisciplinary research discovers that Stonehenge stands at the heart of a vast Neolithic landscape with temples, burial mounds, pits and ritual shrines. As one of the most rewarding archaeological research being done on Stonehenge, the Stonehenge Riverside Project, lasting over 10 years, connects Stonehenge to other Neolithic monuments, i.e. Durrington Wall, the Cursus, Amesbury, Woodhenge and the Preseli Hills in Wales. The person who drew Avebury, Stonehenge and the Rollright stones in1806 similarly tries to connect Neolithic monuments, by drawing them with similar compositional perspective and thus trying to see resemblances in appearance and character. However, there have been long interludes in which theorizing about the function of Stonehenge was done in isolation, not relating Stonehenge to its prehistoric landscape features, that are ‘teeming with previously unseen archaeology’ (Vince Gaffney, 2014).

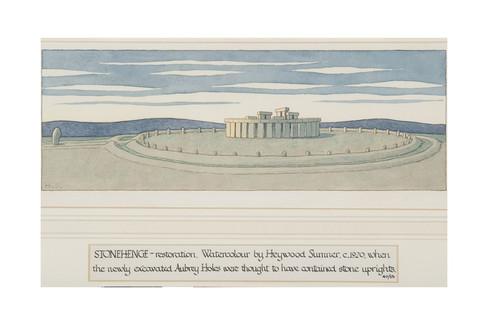

A pen drawing and watercolour by George Heywood Maunoir Sumner (1853–1940) c. 1920.

Visible in this pen drawing of Stonehenge, seen from the north west, are the upright positioned Aubrey Holes, a ring of fifty-six (56) chalk pits, named after the seventeenth-century John Aubrey who identified them. Although the Aubrey Holes date back to the earliest phases of Stonehenge (4th millennium BC), their purpose is still discussed.

Before Pearson’s Stonehenge Riverside Project, Stonehenge has been proposed to a monument to honour Apollo (Hecates of Abdera, 4th century BC), a religious monument for Druids (John Audrey), a monument for the dead (Sir Arthur Evans 1851-1941), an astronomical centre (Sir Norman Lockyer 1836-1920), and an astronomical observatory (Gerald S. Hawkins (1982-2003). Also, Stonehenge has been identified as a Neolithic Lourdes, a place were people with illnesses travelled to, even as far as from Switzerland, as the Amesbury Arches shows, in hope for a cure. Trepanation probably took place at Stonehenge (R. Atkinson, 1920-1994). Despite research and restorations, Stonehenge remains ‘a terra incognita, an icon, occupying one of the richest archaeological landscapes in the world’ (Vince Gaffney).

CONCLUSION

Artworks dating back as far as the 14th century show a varied succession of theories about Stonehenge. Putting all research together holistically and evaluating Stonehenge in relation to neighbouring monuments, offers hope we will succeed in understanding Stonehenge in its different functions. Interpretations of the ritual nature of Stonehenge have changed, expanded, have been refuted and have been upgraded. Having concluded that, is safe to state that Stonehenge has seen a long succession of varied rituals, many of them being related to health, burial and ancestral honouring.

Paula Kuitenbrouwer

This assignment was written for ‘Ritual and Religion in Prehistory’, Oxford Department for Continuing Education, a course Paula thoroughly enjoyed and highly recommends. Copyright 2017.

Paula holds an MA degree in Philosophy and she is the owner of mindfuldrawing.com. Her pen and pencils are always fighting for her attention nevertheless they are best friends; Paula likes her art to be brainy and her essays to be artistic.

Paula Kuitenbrouwer, artist at Utrecht and also at: Etsy and Instagram.

SUPPORTING THIS WEBSITE

May I kindly ask, have you appreciated this essay? Should you have enjoyed this essay and website, please consider supporting my work, website, and art that has fine art, spirituality, and nature appreciation at its heart.

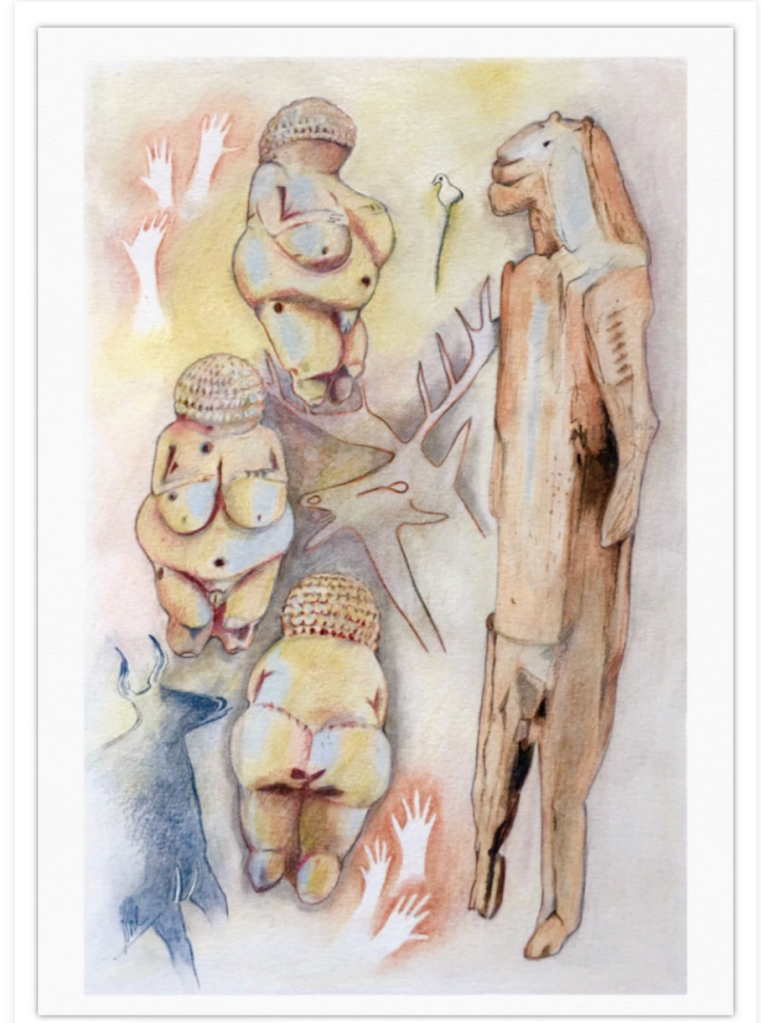

PREHISTORIC ART CARDS BY PAULA KUITENBROUWER

Two (2) Venus of Willendorf and Lionman small art cards with text

Two art cards with text on the back about Venus of Willendorf and Lionman, projected against a background with hand stencils and scenes of Lascaux cave. Lovely as a gift, an altar piece, a bookmark for prehistoric books, a wish card (small space left for adding a short wish). Free shipping.

€10.00

Two (2) Crossed Bison of Lascaux Art Cards

Two large double folded and richly illustrated, professionally printed art cards: one for keeping (framing) and one for sending. Crossed Bison is a famous panel in Lascaux’s prehistoric cave. The awesome beast seem to emerge from a crack in the wall, stampeding toward the viewer with great urgency. Read more about this artwork on my website.

€18.00

Thank You!

[…] A related post on prehistoric female figurines is here. […]

[…] Wings Angel Wings II Lichen and Midwinter Angels’ Wings Welcome to my website that is full of my art and…

[…] Angels’ Wings Angel Wings II Lichen and Midwinter Angels’ Wings Welcome to my website that is full of my art…

[…] with having decluttered our apartment, homeschool library, workroom, and artist’s portfolio, I am now on an adventure to adapt…

[…] with having decluttered our apartment, homeschool library, workroom, and portfolio, I am now on an adventure to adapt my…

Thank you, Paula, for sharing your essay from your research on Stonehenge through Oxford continuing education; it is rich with theory and knowledge. I so enjoy your sharing the results of your studies with your viewers

And thank you, Lois. I have been away for a while, studying this course, for 10 intense weeks. It was worth every page I had to read as this course was massively interesting. It has inspired me greatly. I am now rushing off to your web-blog to see how you have been doing. I expect some lovely spring sketches, for sure!

Paula, I have been involved in other projects plus traveling to Europe giving not much time or energy to do any journal posting. Breaks sometimes give one time to learn, reflect and refresh those brain cells to improve and express those skills in expressing the arts. I am sure your class enriched your knowledge greatly.

Interesting! As an odd little coincidence, I recently read about Merlin and Stonehenge in a novel. It’s a fascinating place, and we seldom see the long history of writing or visuals about the place. Thanks for sharing!